Introduction

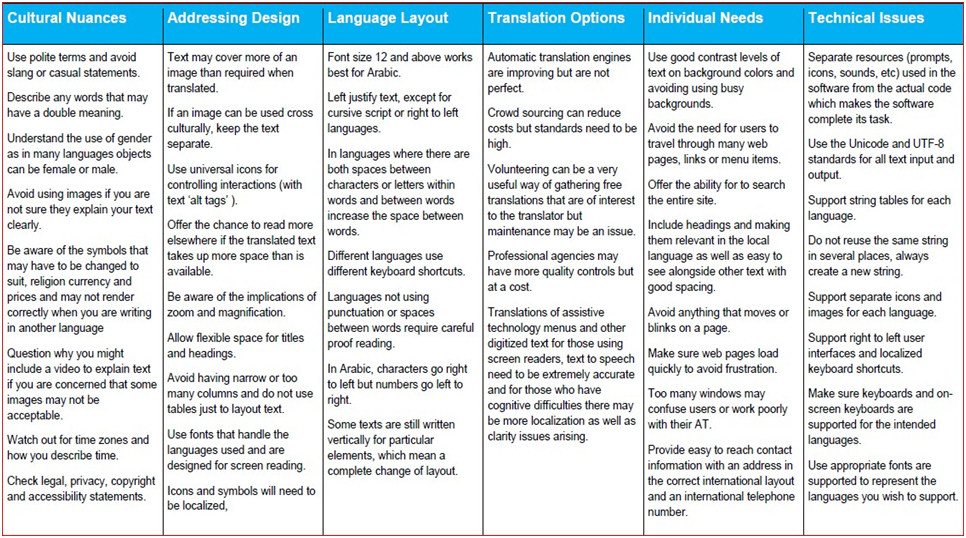

The following units are based upon the localisation framework created in 2013 to support the transference of assistive technologies from one language or culture to another. The units then fully acknowledge the work of EA Draffan, Mike Wald, M. White and N. Halabi. As well as the contributions to the framework made by Erik Zetterstrom and Shilpi Kapoor and the support provided by the Mada Center in Qatar. All units are licenced under the original licence Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).(link is external)

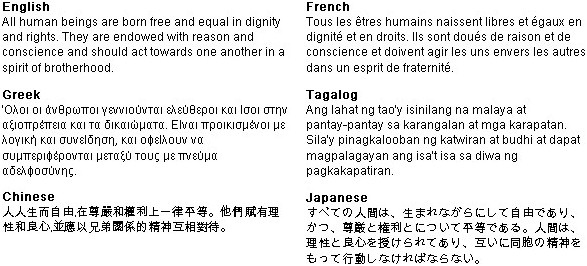

Unit 1: Introduction to Localizing Assistive Technology

This guide is intended to provide you with an overview of how you can make your assistive technologies suit a wide range of users around the world. It is based upon experience of working to develop assistive technologies in Europe, Middle East and the Indian Sub-continent.

We recognize that assistive technology incorporates a wide range of products and services that can be helpful to those with disabilities, not just specialist access tools but also those items that help with personalization such changing the colour of fonts and backgrounds, productivity tools such as word processing packages and free, portable and online tools from the tablet to a plug in toolbar on a browser.

There is nothing new about ’localization’ and how people have attempted to develop computer based products and services to suit individual cultures, languages and environments.

The Localization Research Centre in Eire describes localization as “The linguistic and cultural adaptation of digital content to the requirements of a foreign market and the provision of services and technologies for the management of multilingualism across the digital global information flow.”

Evans (2001) describes it more specifically by saying:

“Localization is the process of adapting a software product to a specific cultural market. This does not only involve translation of the user interface into the local language and supporting appropriate hardware. It also involves taking care of other local conventions such as date, time, currency, number formats, text, images, color symbols, flow of information and product functionality (Russo and Boor, 1998; and Nielsen, 1990). Localization typically involves evaluating the differences between cultures and the problems that are likely to occur because of these differences”3.

It is hoped that others will join in the debate about localization, assistive technologies and linking services, with comments being added to these pages. We would also like to see more case studies in the future and discussions around the issues that can arise when working in languages and areas around the world that are unfamiliar to the developer.

The Guide is divided into a series of short sections, which can be read as independent units or as part of a fuller package related to design, culture and language.

Unit 2 Cultural Nuances

Any definition of culture is complex. But in terms of a disability and assistive technology Ripat and Woodgate (2011) cite a series of authors when they say that:

“…culture refers to the beliefs, values, meanings and actions that shape the lives of a collective of people, influencing the ways people think, live and act. These beliefs, values and ways of understanding are socially constructed and specific to the culture in which they are found”.

There is no doubting the importance of culture in terms of the development and use of assistive technologies. It can be the very thing that prevents the user from adopting their technology wholeheartedly for use in everyday life. If the AT does not fit the individual’s self-perception, and acceptance by others, it is likely to be abandoned. Examples of how the iPad is being used for augmentative communication purposes illustrates how a ‘fashionable’ widely accepted technology is more readily adopted compared to a specially designed communication aid, which lacks aesthetic appeal in the eyes of the user and is considered stigmatizing and thus unacceptable. (Ripat & Woodgate cite Parette et al). The extent to which the device itself is perceived as an “object of desire” within a community will impact upon willing use.

There are those issues relating to technology use linked to gender, status, education, and social class within an individual’s environment as part of the wider perspectives on culture and disability that also need to be considered.

National Cultural Dimensions

Some authors divide the world into different cultural groupings. These include

- Western cultures including Northern America and most of Europe and in some respect, parts of Oceania – Australia and New Zealand with the English language being predominant.

- Eastern and Far Eastern cultures namely Central Asia stretching across Russia on to China and Japan, not forgetting the Indian subcontinent.

- Latin cultures where Spanish is spoken tend to be grouped together, for example Latin America or South America, Mexico and Cuba along with Spain and Portugal.

- Middle Eastern cultures linked to the northern countries of Africa and those from the eastern side of the Mediterranean and Arabia

- Those from the Sahara Desert south including a range of diverse African cultures.

Such cultural groupings exhibit specific dimensions and characteristics which might include:

- Power Distance (PDI) – A high score shows an acceptance of an unequal distribution of power; a low score means power is shared -people view themselves as equals.

- Individualism versus collectivism (IDV) – A high score indicates loose interpersonal connections other than perhaps within families whereas low scores indicate strong ties,care and loyalty within groups.

- Masculinity versus femininity (MAS) – A high score indicates a country where men take on the traditional male role with low scores occurring where women are considered on an equal footing in the workplace.

- Uncertainty avoidance (UAI) -High scoring countries tend to avoid unknown situations and stick to the rules of the land whereas low scorers seek to encourage innovation and individuality.

- Long-term versus short-term orientation (LTO) -High scores tend to mean an acceptance of traditional ways and respect for elders views whereas low scoring groups are willing to try ideas even if the may affect their standing in society in the short-term.

- Indulgence versus Restraint (IVR) – High scoring countries allow the freedom for personal enjoyment whereas low scores show restraint and strict rules about self gratification. (Hostede 200x)

The World Value Survey Cultural Map 2005-2008 presents the world differently where each country is positioned according to the values of its population rather than geographic location.

In this map the “Traditional/Secular-rational values” dimension reflects the contrast between societies in which religion is very important and those in which it is not. Societies with an emphasis towards the traditional tend to emphasize the importance of family ties, deference to authority, with absolute standards and family values. They often exhibit high levels of national pride. Societies with secular-rational values tend towards the opposite preferences.

George et al., (2012) used Hofstede’s dimensions to illustrate how these cultural differences impact on interface design illustrated in the table below alongside the impact the dimensions may have on AT use.

|

|

Score on Hofstede Dimension |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Score |

Low |

High |

|

Dimension 1 |

Power Distance |

|

|

Design – Look and Feel – websites |

Less structured access to information, less focus on expertise, authority and official Logos. Fewer access barriers images of young people (not gender specific) in everyday activities and public spaces. |

Access restrictions. Emphasis on images relating to leaders and large buildings. Symmetrically designed sites |

|

AT Use |

AT user may be considered as expert as the provider when seeking help |

AT expert and elders considered as important in acquisition of advice and skills etc. |

|

Dimension 2 |

Individualism |

|

|

Design – Look and Feel – websites |

Emphasize history and tradition, include socio-political achievements, images of groups and older people. A more formal approach – value social relationships. |

Images of success with an emphasis on action and pictures of individuals. Use of direct language and individual opinions - |

|

AT Use |

AT that promotes independence may not be highly valued – it is more important to see it as part of the whole and working in harmony within the community |

AT is promoted as providing independence as an individual |

|

Dimension 3 |

Masculinity |

|

|

Design – Look and Feel – websites |

Emphasis on visual aesthetics, support cooperation and exchange of information, images of groups of people laughing talking and working together, figurative images, pictures of women. |

Focus on task efficiency, utilitarian graphics, limited choices, highly saturated color images. |

|

AT Use |

AT needs to not only work but also look good plus have a gender and generational fit |

AT provision may differ between genders – not necessarily equal status between genders and age. |

|

Dimension 4 |

Uncertainty avoidance |

|

|

Design – Look and Feel – websites |

Long pages with scrolling and vertical page layout, abstract images, fewer links. |

Restricted amounts of data, formal organization of charts, extensive legalese. Horizontal page layout, more pictures of buildings. |

|

AT Use |

Trial and error acceptance |

Avoids making mistakes and fears showing others where mistakes are being made. |

|

Dimension 5 |

Long term orientation |

|

|

Design – Look and Feel – websites |

Emphasis on current events, clear strategic plans, fast efficient task execution. |

Photos representing a history of events or activities and images of creators or the establishment. Looks to the future over a long period. |

|

AT Use |

Trialing the latest technology tends not to cause issues as long as it has possible benefits. |

AT must be considered in the light of accepted behaviors within society at the time of provision. |

|

Dimension 6 |

Indulgence |

|

|

Design – Look and Feel – websites |

Symbols of status important, rewards clearly illustrated for work well done but restrained. |

Allows fun elements to appear with rewards appearing that are not necessarily linked to material items. Objects need to fulfill their purpose not status. |

|

AT Use |

Prefers to use items that are used by others and are respected. |

Accepts items that may not have status but suit the needs of the user |

A comparison of all the countries and their rankings can be found on Hofstede’s website or can be read about in a paper made available by Westwood Schools(link is external) at

http://westwood.wikispaces.com/file/view/Hofstede(link is external).

Unit 3 Cultural Appropriateness

This Unit explores the importance of cultural awareness of cultural etiquette and understanding

Whilst the layout of multinational business websites and menu items for software seem to be growing increasingly similar, research and experience suggests that many users prefer a style that is localized to their community over standard corporate branding.”(Segev et al, 2007). Even websites designed for global companies have developed a distinctive localized feel reflecting diversity of content, written language style and use of meaningful media and colours.

Patterns and Styles of Written Language

There are social nuances related to greetings, gender and religion in written language, that all need to be considered when developing assistive technologies. When implementing text to speech, it is important to understand the importance of accent and dialect which may impact on users when they differ from the written word. For example, Modern Standard Arabic read aloud with synthesized speech has a very different sound compared to conversational Arabic – a case of diglossia. In fact, most languages have different forms of writing compared to speech which need to be considered in terms of formalities and etiquette.

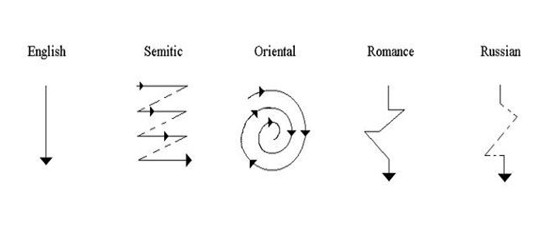

Robert Kaplan (1966)2(link is external) described patterns for the way authors write in their own language and has illustrated this by a series of diagrams, they can help in explaining why some text appears very linear and others may have more circumlocution, tending to go round a subject rather than being direct.

Kaplan’s models of contrastive rhetoric

Written English is more concise than its spoken form, but not a completely different experience as may be the case with Arabic written text compared to its conversational style. Arabic, Hebrew and other Semitic languages may have more gracious introductions when writing begins and ends with some repetition. Kaplan shows Romance and Russian writings as having the possibility of wandering off topic with additional information.

Appropriate social nuances and legal issues

In some cultures. simple introductions in text such as ‘Hi’ or ‘Hello’ would appear abrupt and, as in Arabic, the first few words may take on a more formal note such as “Peace be upon you and God’s mercy and blessings” so it is important to be familiar with writing style that is most commonly seen in each country.

The way people are addressed also differs and affects the use of language not only in the terminology such as the use of titles, but also in prefixes and suffixes added to names and even additional hyphenated words such as in the Japanese title of -san as in Peter-san.

The laws about accessibility and ease of use for those with disabilities also vary but it is important to take care of these issues and ensure fairness of access. To keep written language appropriate it helps to:

- Remember to be polite at all times and avoid slang or casual statements

- describe any words that may have a double meaning

- understand the use of gender as in many languages objects can be female or male rather than neuter as in the use of ‘it’

- avoid using images if you are not sure they explain your text clearly and beware of the map that is out of date which is linked to an address.

- be aware of the symbols that may have to be changed to suit, religion currency and prices and may not render correctly when you are writing in another language.

- question why you might include a video to explain text if you are concerned that some images may not be acceptable. Take care when showing hand gestures or other body parts such as the feet that may be considered rude when shown in certain positions.

- watch out for time zones and how you describe time, always offering alternatives when thinking of the world’s time clock.

- Be conscious of how terms may carry cultural norms, such as “independence”.

- Check legal, privacy, copyright and accessibility statements.

Demographics

Understanding the demographics of a given market are important. The demographic balance may have a real impact upon design. For instance, in some parts of the world the age of technology users is shifting as older people – those 65 or more make up nearly a quarter of the population in countries such as Japan, parts of Europe and the USA. This has an impact on the way we present technology as well as the content. Many people develop dexterity, visual, hearing and understanding difficulties with old age and need the support of assistive technologies in their own languages and to suit their personal environments.

Often an older user base may require more time, and good usability is essential, so it is important to think about:

- How quickly a screen loads and the impact it might have on older computers and poor connection speeds as well as the frustration levels of the user.

- Good contrast levels of text on background colours and avoiding busy backgrounds for important text is often mentioned under accessibility but it is useful if there is important content.

- Letter spacing and easy to read text which has been discussed earlier

- Clear information on the first page of the online service or web page or instruction manual to tell the user what to expect.

- How many windows are going to open with the use of extraneous links and plugins – too many not only cause confusion but they can be slow to open and hard to use with some Assistive Technologies.

- Broken links or pop-up dialog boxes that return a message that is not easy to understand or appears in another language such as a ’404 error page’ on a website.

- Easy to reach contact information with an address in the correct international layout and an international telephone number – preferably in addition to any free number, as this may not work from outside the country. Links to a map can also help in some circumstances.

- Avoiding the need for users to travel through many web pages, links or menu items to get to their goal. Keep navigation clear, quick and easy and make buttons and links clearly visible by shape, colour and consistent style.

- Always offering the ability for someone to search for items not just browse lists etc. It is possible to use the Browser search when working on the web but only for that page and not all individuals know this is possible.

- Headings and making them relevant in the local language as well as easy to see alongside other text with good spacing.

- Anything that moves or blinks on a page as this can be a distractor and it is important to avoid bright and conspicuous advertisements that draw the attention away from content unless that is what you require. It is important to check the type of advertisements that are appropriate for the country of presentation.

Alternatively, in many African countries there is an increasing young population coming online. They are often using mobile phones to surf for information, and there remains a sophisticated youthful set of technology users across the globe who enjoy working with vibrant, colourful technologies containing increasing amounts of multimedia and fast-paced content. This does not mean that usability and accessibility along with localization should not be considered in the design and development cycle.

Small byte sized chunks of clear information with good graphics and alt tags, can help everyone and with responsive design techniques this should be possible in any cultural environment using any type of technology.

Unit 4 Addressing Design

McDonalds’ home pages on 3rd November, 2013 Top left to bottom right – Germany, Russia, Japan, Spain, China, Qatar.

Most users of technology, including those using assistive technologies, prefer to have products designed to be functionally easy to use but also attractive to look at, quick to navigate with consistency of fonts, colours and general style.

In considering website design, 76% of consumers said the most important factor was that the website made it easy for them to find what they wanted. Here are some key points that might help. (Hubspot 2011)

Key Points

- Think carefully about image sizes that incorporate text – text may cover more of the picture than required when translated or change the shape of a menu item or even become truncated.

- If an image can be used cross culturally, keep the text separate to avoid extra work and enhance accessibility.

- Use universal icons for controlling interactions with ‘alt tags’, so for example ‘play and rewind’ have the same shape button whatever the language.

- Allow text to reflow – offer the chance to read more elsewhere if the text when translated takes up more space than is available in a set area. Be aware of the implications of zoom and magnification.

- Allow flexible space for titles and headings, if these are part of the menu system.

- Try to avoid having narrow columns or too many columns and do not use tables just to layout text as this will not help screen readers and will be lost in a text only view. Only use tables for content data when necessary.

- Choose font sets and styles carefully as some may not be recognized by certain languages and not all are designed for screen reading rather than paper based reading. For example, angular and serif fonts may look good on paper but reduce readability when seen on small low resolution screens such as the mobile phone. Examples of useful sans serif fonts would be Arabic Transparent and Simplified Arabic Fixed rather than Koufi or Andalus or in English Helvetica, Arial and Verdana rather than Times New Roman.

- Icons and symbols will need to be localized, in particular those related to currency using the correct positioning. For instance in Sweden the code may be SEK 1957,50 (1957 Swedish crowns and 50 öre), 1 957,50 Swedish krona (kr) or 1957,50:- Some symbols used such as checks in check boxes may have different meanings. There is the much quoted wikipedia example of “In Finnish,

stands for väärin i.e. “wrong”. (The opposite, “right”, is marked with , a slanted vertical line emphasized with two dots).”

stands for väärin i.e. “wrong”. (The opposite, “right”, is marked with , a slanted vertical line emphasized with two dots).” - Never hard code date, time or currency formats - use a code library that has localized files for each required area as even the start of the week may be different in your chosen countries. There are a series of standards dealing with these issues such as ISO 8601.

Unit 5 Language

Language localization is not the same as a direct translation such as that offered by Google Translate nor is it quite the same as internationalization in terms of product development as can be seen in the diagram below, where items and services are developed for a general global market. Testing AT (products and support systems) for localization issues during the design and development phase with those who have disabilities is sometimes hard to achieve. However, it is crucial for success and this must be undertaken in the environment in which the tools and services will be used.

From GALA http://www.gala-global.org/why-localize(link is external)

The globalization and internationalization of AT design and development is rapidly increasing – a few years ago text to speech was available in a limited number of languages now companies developing computer generated or synthetic speech systems are offering over 40 languages with over 100 voices being available. In terms of assistive technology, screen readers for those with visual impairments are only available in 28 languages. This is also true of desktop text to speech programs that can support those with reading difficulties.

56.2 percent of consumers say that the ability to obtain information in their own language is more important than price. – (Common Sense Advisory, Can’t Read, Won’t Buy: Why Language Matters on Global Websites, 2006) Why Localise (GALA)

Easy Language Checks

- Localize for meaning not just choosing word for word translation and ask a local to proofread the outcome as well as using the appropriate language and voices for text to speech or a screen reader to ensure easy reading for those with print impairments.

- Keep the message simple – clear statements in the active voice e.g. ‘Select the arrow icon to start the recording’ rather than ‘the recording will be activated when the arrow icon has been selected.’

- Keep complex terminology consistent and provide a glossary - assistive technology may be known as supporting technology (ondersteunende in Dutch) in some areas of work, with differences in health and education. Terms such as ‘handicap’ may be accepted in some languages and special needs or impairment may be used others – UK British may use the term ’disabled person’ – USA ‘person with disabilities’.

- First person and second person rather than third – Academics encourage the use of third person but when writing instructions or simple guidance it may be easier to translate when first and second person is used. e.g. ‘You can increase the volume to listen to quiet speech‘ rather than ‘Quiet speech may mean that the volume should be increased‘.

- Avoid metaphors, colloquialisms, slang, acronyms, e.g. It is raining cats and dogs

When using the local expression in Dutch would be ‘it is raining ‘pipe stems’ or in French ‘ropes’

- Check spelling and grammar matches that of the standardized written language of the country such as Modern Standard Arabic

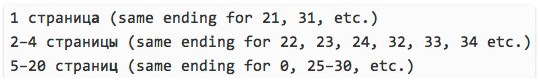

- Beware the gender and quantity and how this can change a word or the context of the word. In English words rarely change to show gender so we may think of a ‘ship‘ as ‘she‘ but we do not change the word or the article ‘a’ or ‘the‘ to show that gender, whereas in French it would be male and ‘le bateau’ . To show a quantity in English the letter ‘s’ may be added but in Russian, according to www.ibabbleon.com(link is external) the ending changes depending on the number of pages.

- Punctuation use differs across languages and needs to be used carefully. Abbreviations, acronyms or short forms may be recognized by the use of the full stop or period in English but not for instance in Arabic. Adding a full stop between individual letters to show a short form can aid the screen reader or user of text to speech, as otherwise these are read as whole words.

- Watch out for the apostrophe. Not only can it cause problems with coding, but it can also be hard to replicate in another language. In English it may be used where letters are missing such as ‘it’s’ for ‘it is’ or where something belongs to someone – John’s coat which can be said as ‘the coat that belongs to John’

- ‘The’ can be used incorrectly at times in written language – In English you may say ‘the 5th of March, 2013‘ but you would write ‘5th March, 2013‘ in French the ‘le’ or ‘the’ stays in place.

- Take care with accents and diacritics if required for pronunciation purposes such as in Arabic – Their use can help with the accuracy of text to speech and screen reading but they are often avoided on web pages to reduce clutter. Most literate individuals have internalized the language so can read sentences without the need for diacritics where they replace short vowels such that a sentence written as ‘ I cn go to the cmpng shp‘ could be read accurately even though ‘shop‘ may be ‘ship‘.

- Check how numbers, measurements, time and dates are presented and make sure they appear correctly on the screen when saved in the translated language. A date such as 3/4/2013 in America is 4th March, 2013 and in UK represents 3rd April, 2013.

- Make sure you are aware of the protocols for addresses. Address layout differs widely between countries, postal codes or zip codes may not lead precisely to a house, but may relate to an area. Post Office boxes may be used rather than house addresses where people go to collect their mail such as in villages in Kenya. In some areas street addresses are limited so at times landmarks may be used as guides rather than formal addresses.

(From Wikipedia)

- If you offer an alphabet search system note that not all alphabets have corresponding letters to A-Z and some will have several options for one letter and differ visually depending on their position in the word such as in Arabic.

- Avoid the use of technical or localized words that are not in the dictionary of the language you are translating.

- Do not make it hard for the translator by using overly simple but ambiguous links in web pages such as ‘read more‘ or ‘click here‘ as not only does this not help the screen reader user (who will not know where he or she is going) but also the translator who needs to know what is going to be read or the link title.

- Know your audience and understand their knowledge and literacy levels.

Language impact on Layout

The layout for any screen will need careful localization treatment as many languages take up different amounts of space and some require larger fonts and characters than others. For instance, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and French have sentences that are up to 25% longer than those written in English. Allow plenty of space within edit boxes and for command buttons that will also change size depending on the language.

Omniglot looking at different languages and the effect on text length

(http://www.omniglot.com/language/articles/multilingual_websites.htm(link is external))

Cursive and Arabic characters need to be larger for easier reading especially if diacritics are included.

Key Points

- Choose a font for your work that has an extended character set to include the accents and if possible the diacritics.

- Font size 12 and above works best for Arabic and other cursive scripts as this increases readability.

- Choose font styles carefully for screen reading rather than paper based reading. For example, angular and serif fonts may look good on paper but reduce readability when seen on small low-resolution screens such as the mobile phone. Examples of useful sans serif fonts would be Arabic Transparent and Simplified Arabic Fixed rather than Koufi or Andalus or in English Helvetica, Arial and Verdana rather than Times New Roman.

- It can help those with reading difficulties to left justify text so when viewed overall there is a jagged edge to the content and users can see where they have reached in their reading. This may not be the case in cursive script languages where there are specific elongating characters which act as connectors. By fully justifying text may make it easier for readers to recognize characters and diacritics.

- In languages where there are both spaces between characters or letters within words and between words (such as in Arabic) it helps to increase the space between the words to help screen reader users and those with print impairments or reading difficulties.

- Don’t forget that different short cut keys may be used in the different languages so if you wish your users to have access to text edit forms and they are keyboard only users you may find that ‘Ctrl+B’ or ‘Command+B’ does not make the text bold – in German for example it may be ‘Strg+F’ namely ‘Steuerungstaste-fett’ which would be Ctrl+F or ‘Command+F’ which is ‘Find’!

- Spaces are used after a word in English and hyphens may be used between words – Chinese, Korean and Japanese character breaks occur at any time and care is needed no to impact on meaning – spaces are not linked to words necessarily – the same may be true with Arabic sentences. Punctuation in these languages and Arabic vary in the amount used so careful proof reading is required.

- Don’t forget bidirectional languages – so for Hebrew and Arabic letters go right to left and numbers left to right or there may be a mix! This can have an impact menus as well as content especially for technical terms when coding.

- Some texts are still written vertically which means a complete change of layout such as is illustrated in the image below of a Chinese Newspaper.

Example of a newspaper article written vertically in Traditional Chinese with a left-to-right horizontal headline. Note the rotation of the Latin letters and Arabic numerals when written with the vertical text. (wikipedia)

There are many ways to translate and contextualise text for differing communities. In determining your approach you should bear in mind that:

- Automatic translation engines are improving but are not perfect

- Crowdsourcing can reduce costs but standards need to be high

- Volunteering can be a very useful way of gathering free translations that are of interest to the translator but maintenance may be an issue

- Professional agencies may have more quality controls but at a cost.

- Translations of Assistive technology menus and other digitized text for those using screen readers, text to speech need to be extremely accurate and for those who have cognitive difficulties there may be more localization as well as clarity issues arising.

Unit 6 Images, symbols and colour in design

Images

Images carry many subtle cultural messages within them. Such messages can have a significant impact on the ease of use and comfort for users. Pictures or images may have negative connotations that may repel viewers, and should be considered carefully.

For example, if a wayfinding site in a mostly Muslim populated country used pictures of scantily clad women in bikinis, disco dancing and beer drinking to denote “beach” or “resort”, the graphics may well be considered inappropriate. When including pictures of people it is wise to tailor these to what the target audience will look positively upon. A picture of a teacher behind a desk in a classroom may feel familiar in some communities and extremely old fashioned for others. The selection of pictures can either help a user to relate to your content and message or create additional barriers.

Taking care to understand the cultural norms related to people, places and events can be very important in selecting images within your design, especially where these have strong historic and cultural contexts. An image in one culture that denotes freedom or liberation might be perceived as loss by those who supported a more conservative approach.

Such issues are further complicated when images become more abstract such as the use of symbols to convey meaning and action.

Symbols

Symbols can be easily misinterpreted across cultures. Icons using fingers such as an OK sign or thumbs up may mean different things to different cultures. Western symbols do not always mean the same elsewhere. For example, the representation of a house to refer to a home page, or a letterbox to mail. The use of animals in logos can have unintended consequences. For example, pigs are considered unclean in the Middle East and cows as holy in India.

The issue is made clearer in a study of software icons by Knight et al (2008) For instance the icon for “under construction” on a webpage was variously interpreted as being related to “traffic safety,” “barriers,” and “warnings” by 74% of users from the Far East. Similarly, interpretations of the Search icon, was interpreted within the themes: “locked access,” “magnification or zoom,” and “secret and confidential.” The Search icon uses an image of a magnifying glass to represent the search function but does not rely on a verbal association between the name of the object depicted and the represented function. However, many of the participants may have assumed the function associated with the representation, a magnifying glass, to be magnification. For participants who were unable to identify the icon, the abstract style may have detracted from the clarity of the depicted subject.

They further suggest that

“How an icon operates graphically – whether symbolic, abstract, or representational – may influence interpretations of meaning. Symbolic icons, usually abstract images, represent culturally agreed upon meanings that must be learned, and may be difficult to use across cultural contexts if meanings are not internationally agreed upon. Recognition of abstract icons, graphically minimal representations, may depend on the degree of resemblance to the subject or object depicted. Representational icons serve the purpose of describing with some degree of accuracy what is depicted visually. Drawbacks associated with representational icons relate to the tendency for features relevant and irrelevant to the message to be conveyed through the single pictorial representation. Representational image features such as shape and colour often vary across cultures. A mailbox has a different shape and colour in North America, England, and Morocco”

The use of symbols in software designed to support those with language impairments or communication needs, also needs to take account of the cultural context within which communication takes place.

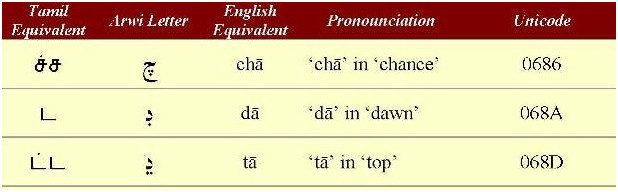

In developing an AAC symbol library for Arabic speakers, the Tawasol project found that the design of symbols imported from the west was a significant barrier to effective communication, when the symbol no longer reflected the experience of the user.

This is demonstrated in the figure below

In this figure we observe the need to look at forms of dress, of direction, of physical features, to consider local norms in the environment and to include religious and cultural customs including food within the symbol set.

Colors

Colors strongly convey cultural meaning. Whilst choosing the wrong color for a logo or background will not always have disastrous consequences, they can be readily avoided. in Japan white is commonly associated with mourning, in China red is auspicious, and across Africa certain colors represent different tribes.

Some of the values attributed to color, within different cultures are described below

- Blue

Blue has many positive associations. In North America and Europe it represents trust, security, and authority, and is considered to be soothing and peaceful. But, can also represent depression, loneliness, and sadness (hence having “the blues”).

In some countries, blue symbolizes healing and evil repellence. Blue eye-shaped amulets, believed to protect against the evil eye, are common sights in Turkey, Greece, Iran, Afghanistan, and Albania. In Eastern cultures, blue symbolizes immortality, while in Ukraine it denotes good health. In Hinduism blue is strongly associated with Krishna, who embodies love and divine joy.

- Green

In Western cultures green represents luck, nature, freshness, spring, environmental awareness, wealth, inexperience, and jealousy. Green is an emblematic colour for Ireland, which earned its nickname “The Emerald Isle” from its lush green landscapes.

Green has traditionally been forbidden in Indonesia, whereas in Mexico it’s a national colour that stands for independence. In the Middle East green represents fertility, luck, and wealth, and it’s considered the traditional colour of Islam. In Eastern cultures green symbolizes youth, fertility, and new life, but it can also mean infidelity. In fact, in China, green hats are taboo for men because it signals that their wives have committed adultery!

- Red

Or many in the west, red symbolizes excitement, energy, passion, action, love, and danger. But is also associated with socialism and revolution. In some Asian cultures red is a very important colour, symbolizing good luck, joy, prosperity, celebration, happiness, and a long life. As it is an auspicious colour, brides often wear red on their wedding day and red envelopes containing money are given out during holidays and special occasions.

In India red is associated with purity, sensuality, and spirituality. On the other hand, some countries in Africa associate red with death, and in Nigeria it can represent aggression and vitality. It’s considered a lucky charm in Egypt and symbolizes good fortune and courage in Iran.

- Yellow

In Western cultures, yellow is associated with happiness, cheeriness, optimism, warmth (as the color of sunlight), joy, and hope, as well as caution and cowardice. In Germany, yellow represents envy, but in Egypt, it conveys happiness and good fortune.

- Orange

Orange represents autumn, harvest, warmth, and visibility in Western cultures. In Hinduism saffron (a soft orange color) is considered auspicious and sacred. In the Netherlands orange is the colour of the Dutch Royal family, while it represents sexuality and fertility in Colombia. In Eastern cultures orange symbolizes love, happiness, humility, and good health. Buddhist monks’ robes are often orange.

- Purple

Purple is often associated with royalty, wealth, spirituality, and nobility around the world. Historically in Japan only the highest ranked Buddhist monks wore purple robes. Purple is also associated with piety and faith, and in Catholicism, penitence. However, in Brazil and Thailand purple is the color of mourning. It’s also a colour of honour, the Purple Heart is the oldest military award still given to US military members.

- White

In Western cultures, white symbolizes purity, elegance, peace, and cleanliness; brides traditionally wear white dresses at their weddings. But in China, Korea, and some other Asian countries white represents death, mourning, and bad luck, and is traditionally worn at funerals. In Peru, white is associated with angels, good health, and time.

- Black

In many cultures black symbolizes sophistication and formality, but it also represents death, evil, mourning, magic, fierceness, illness, bad luck, and mystery. In the Middle East black can represent both rebirth and mourning. In Africa it symbolizes age, maturity, and masculinity.

In designing software for use across cultures and communities it can be beneficial to understand the cross-cultural meanings of colours. By knowing the symbolism of different colours around the world there is less chance that your intention is misinterpreted.

Unit 7 Technical Issues

Before considering a development environment for your software or contemplating localizing existing software; separate resources, such as strings, images, and videos, from your code; move them into separate, resource-only files.

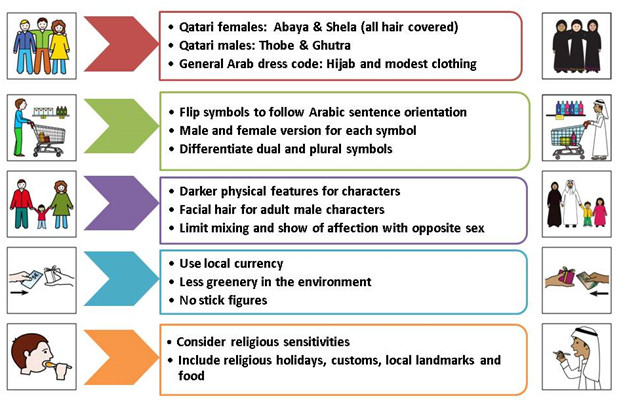

Check that Unicode is supported and when localizing existing software check that the string type used supports Unicode. Unicode is a character encoding standard supporting most known written languages. Each known character receives a unique identifier; this number can be several bytes long. To achieve compatibility with the older ASCII format the Unicode Transformation Format 8 bit (UTF-8) was invented. UTF-8 varies in length but the ASCII characters all have the exact same code in UTF-8.

The most basic tool to support multiple languages is the use of string tables, where each string used in the software is given a unique string identifier. Each language has its own table containing the unique string identifiers and the string contents in the specific language. It is a good idea to use descriptive names and a naming standard for the string identifiers. Do not reuse strings! For example the string “on” could be correct in two separate places in English but in another language two different words could be required.

When the language currently used by the application is communicated to other applications the language codes specified by ISO 639 should be used. In some cases it is also necessary to specify which character set is being used, for example in HTML using the charset parameter.

Is the date 12/6/103, 12th June 2013 or 6th December 2013?

The format used for dates and times used in the world are many, it is recommended to use a standardized form when storing this data, for example RFC 3339 defines date and time formats on the internet. Each user should have their date and time displayed to them and be able to enter date and time in their desired format.

When localizing, icons and images also need to be changed to adapt to the specific culture.

Make sure the development environment allow for different icons and images for different locales. Typically software development environments use resource files to bundle all content for a specific locale. It is a good idea to make sure that your images do not contain any non-decorative text as it would require a new image for every language and more important this text would not be read by a screen reader. (see Unit 3)

The user interface itself may need to be adapted to handle right to left languages or even vertical text. Thankfully most modern development environments can adapt the user interface to a right to left environment by checking a box. Adapting to right to left basically involves moving user interface components such as menus, input boxes, maximize button, etc to the opposite side and switch them to right to left input/output.

Picture: Arabic user interface of the ZoomText Magnifier by Ai Squared.

An often overlooked part of the user interface are keyboard shortcuts, these also need to be localized. Also make sure physical and on-screen keyboard are supported in the desired languages on the target platform. If either is unsupported the software should provide it.

In order to properly display the desired languages special fonts could be needed. Make sure the target environment has fonts supporting all the languages used in the software, if not appropriate fonts need to be shipped with the software.

In some parts of the world it is common to use the English version of the operating system and use software in the local language where available. The reason for this practice is twofold; user have started to use the English version before a version in the local language was available and/or the user lives in a bilingual environment. Due to the latter it is important to allow the user to easily change the language used.

Summary

- Separate resources from code.

- Use Unicode and UTF-8.

- Support string tables for each language.

- Support separate icons and images for each language.

- Support right to left user interface.

- Support localised keyboard shortcuts.

- Make sure keyboards and on-screen keyboards are supported for the intended languages on the target platform.

- Make sure appropriate fonts are supported.

- Allow the user to easily change the locale of the software.

Unit 8 Individual Needs

In countries such as Japan, parts of Europe and the USA. the age of those using technology is shifting with older people (those over 65) making up nearly a quarter of the population. This has an impact on the way we present technology as well as the content. Many people develop dexterity, visual, hearing and understanding difficulties with old age and need the support of assistive technologies. When one includes those who have developmental disabilities some say over 25% of the population in these countries need personalized technologies suiting their language skills and individual environment.

The Nielsen Norman Group: ‘Beyond ALT Text’ research (2001) with disabled individuals found that “the usability issues relating to accessibility are so strong that they dominate the findings and turn out much the same in different countries.” The research showed that when surfing for particular websites sighted participants who use no assistive technology were:

- about six times more successful at completing tasks than people using screen readers

- three times more successful than people using screen magnifiers

Key Points

Providing good usability alongside accurate localization can aid accessibility and address many individual needs. Examples of good practice when building products and web based services include:

- good contrast levels of text on background colours and avoiding busy backgrounds for important text is often mentioned under accessibility, but it helps readability for all.

- avoiding the need for users to travel through many web pages, links or menu items to get to their goal. Keep navigation clear, quick and easy and make buttons and links clearly visible by shape, colour and consistent style.

- always offering the ability for someone to search for items not just browse lists etc. It is possible to use the Browser search when working on the web but only for that page and not all individuals know this is possible.

- including headings and making them relevant in the local language as well as easy to see alongside other text with good spacing.

- avoiding anything that moves or blinks on a page as this can be a distractor and it is important to avoid bright and conspicuous advertisements that can be distracting. It is important to check the type of advertisements that are appropriate at a local level.

- tests to see how quickly a page loads and the impact it might have on older computers and poor connection speeds as well as checking individual frustration levels!

- letter spacing and easy to read text which has been discussed in Language impact on Layout

- Clear information on the first page of the online service or web page or instruction manual to tell the user what to expect.

- checks for how many windows are going to open with the use of extraneous links and plugins – too many not only cause confusion but they can be slow to open and hard to use with some assistive technologies.

- testing time to check broken links or pop-up dialog boxes that return a message that is not easy to understand or appears in another language such as a ’404 error page’ on a website.

- easy to reach contact information with an address in the correct international layout and an international telephone number – preferably in addition to any free number, as this may not work from outside the country. Links to a map can also help in some circumstances.

Accessibility, usability and assistive technology led localization does not mean ‘dull and without interaction’. It is still important to work with vibrant, colorful websites containing multimedia and exciting content as these features can come with alternative formats and hidden hooks for screen reader and keyboard only users that often help others. Webaim provide practical advice about web product accessibility.

Small byte sized chunks of clear information with good graphics (with alt tags) can help everyone and with responsive design techniques this should be possible in any cultural environment using any type of technology.

Unit 9 Delivering with Partners

The development of assistive technologies that are designed to support diverse languages and cultures, is not something an AT company can undertake alone. It requires a combination of technical skill, depth of understanding of language and cultural nuance, and a funding or business model that ensures that the solution is made available with mitigated risk to all concerned.

As new markets emerge, and assistive technology becomes a global product, the partnerships will become critical to the successful uptake of the products by new users. Clarity will be required in the roles and responsibilities of partners both in bringing the product to market and moreover in the long-term production, marketing and support for the new solution.

Selecting partners

- Potential Reach

In determining partners it is important to agree on the potential reach of the planned product. This has to be realistic and honest, no single product will ever meet all of the aspirations and needs of a group of disabled people. We may need to consider what similar products might exist now or in the immediate future, and the extent to which choice is seen as constructive in what may be an emerging market.

Importantly the product brief must have a shared understanding that reach may be about supporting some needs of lots of people, or a much greater depth of impact on a smaller group. Sometimes software stands alone, or can be used to enhance access to a range of hardware platforms. Al of these issues must be taken into account in determining the potential reach of the product

- Technical skills

There is a need to understand the level of technical skill held within the partners. This may be a single person, it may be a team or it may be dispersed across sub contractors or volunteers. In choosing projects there is a need to understand how many people will be involved, is there a risk related to staff turnover and how will those working on the project be involved in the overall process. Clarity of understanding around both the level of technical skill and the way it is organised will be important in ensure there is a shared understanding of risk and agreed mitigations in the event of skill loss.

- Experience of working across Language and Culture

It is challenging for a project to be run and co-ordinated if all partners are inexperienced at working with different languages and cultures. Understanding the track record of partners in successfully bringing products to market to meet different language needs is essential in determining the extent to which resources can be committed and the levels of reporting required. That experience does not have to be in the language with which you wish to work, many of the issues of localisation are similar for different languages, and successful experience with one language may well suggest a willingness to understand the culture of the anticipated market, even if it is one that has not been encountered before.

- Clarity of Roles and Resources

Projects will involve two or more partners, it is important that any and all partners understand not only their role in the project, but also the dependencies that exist based upon the successful delivery of information and code. This may be quite obvious for instance if one partner has a remit for user testing of early and beta versions, and there may be an understanding that a lack of delivery of feedback will potentially halt the creation of code, but their may be a lack of understanding of the impact of smaller tasks such as final screenshots, which if not available may limit the creation of training materials, launch collateral and ultimately delay product launch and marketing.

Making clear statements about who has responsibility for a phase of the project, who has leadership of that work package and the deliverables required from others is going to help significantly in ensuring successful completion, but coupling this with a plan to address any delays in delivery will be important also. An example emerged in one project where training manuals were printed in one country and then delayed at customs for several weeks, by ensuring that designs were created in a shared software package, that electronic files were held in the cloud and that facilities for local printing were available the impact of this was considerably reduced.

- Business model and Funding

One of the most important stakeholders in the project will be the funder. There are a range of funding models that may be considered.

- Grant Funding

- Pre-Purchase

- Seed funding with shared IPR

- Joint funding with shared revenues

A decision as to which of these models is most appropriate may be determined by a range of factors which might include

- Level of investment required

- Level of risk to partners

- Prior IPR and ownership of source code

- Agreed license for publication

- Level of commitment to maintain and update code

- Commitment to promote

- Commitment to provide technical support

The final decision as to the best funding model will be related to reducing the risk of producing a product in a new market, but will also consider the nature of a partnership after launch, who will promote ? who will maintain code ? and who will provide first line technical support and user training ?

There is no single correct model for all projects, in our experience a mixed model depending on the nature of the anticipated deliverable was the most effective in producing a range of Arabic assistive technologies.

Launch and beyond

Relations and partnerships should not finish at the point of handover of a product for use within a community. The launch of a product is the start of a new phase of the project if it is to be successfully implemented. The same care regarding roles, responsibilities and dependencies should be taken at this stage as was taken at the earlier phase of product design.

Most especially it should be agreed :-

- What is the model of distribution within the region ?

- In what format is the product delivered (CD/USB/Download) ?

- What is the first line of technical support for a new region and how is it escalated if required ?

- Who will provide any training and under what licence are training materials made available ?

- What is the agreement for product evaluation and bug fixing ?

- What is agreement around the potential for future shared projects ?

- What is the agreement around shared use of logos and brands ?

But ultimately this leads us full circle, if a trusted relationship between partners has been established prior to launch the that relationship can carry over into the post launch phase. It may be that at this stage a new partner may need to be introduced (such as regional distributor) and once more care should be taken to build relations and clarify expectations Partnerships are critical to the delivery of a successfully localised AT product, an understanding of stakeholders and cultural norms will be vital in building a sense of trust and commitment to the end result.

Unit 10 Case Studies

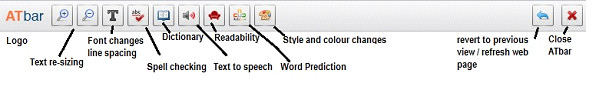

1 Arabic ATbar

A browser based toolbar with options to personalize web pages to assist reading and text input.

The ATbar works with any desktop browser. It is a toolbar that does not have to be downloaded but can be added as a favorite or bookmarklet and allows users to personalize the way they read accessible web pages. It was originally designed as a result of the comments made by students on the LexDis project at the University of Southampton, who found it difficult to read web pages without their assistive technologies. These were mainly dyslexic students who didn’t always have their text to speech software available on the network or in the library.

The plugins on the toolbar allow for the increase or decrease of font sizes, changes to text color and font style, increased line spacing and different colored backgrounds. The students didn’t wish to enlarge pictures at the same time as text so although it is possible to ‘zoom’ in any browser this additional support for the text was felt important. It is also possible to toggle a colored overlay in pink, green, blue and green. The text to speech works when you highlight the text as does the dictionary with single words, which offers definitions from Wiktionary. There is also the ability to use word prediction if typing is slow and the spell checker for the forms that do not offer this feature.

Each of these features is a separate plug-in and there is the facility for not only developing plugins and testing new plugins but also for linking to other plugins via the marketplace, so the complete toolbar can be changed or personalized to suit a user’s needs. This means that the toolbar is highly flexible and it also has its own version control system, and bug tracking and constant updates.

The development of the toolbar occurred over two years and was launched on to the University of Southampton website via the accessibility tools menu. The statistics for uses, as it is only possible to track the number of times the toolbar is downloaded or added to a web page as embedded code has now reached over six million.

The challenge of localization came when the Mada Center in Doha asked for the toolbar to be developed in Arabic. This was a culture, language and environment with which none of us were accustomed. One of the most important things was to immediately set up a very clear tracking system (Github) and make use of a blog to communicate progress. This proved to be very helpful as it provided a diary of events linked to the development and the issues that arose over time. We have been able to use it for many of the links in this case study.

We also provided a wiki page with instructions for each plugin in Arabic. We found that Media Wiki and WordPress were not only accessible to most assistive technologies, including screen readers, but also easy to adapt to the Arabic language with its written form being bidirectional but mainly right to left (links to a useful article on the subject). One of the major issues was the fact that when using a language that goes in the opposite direction to the one you’re used to there is a tendency to forget which side of the menu system the language should appear from. It should also be noted that numbers in Arabic go from left to right and mixing Latin and Arabic alphabets is not conducive to easy spacing on a page. There were times when dialogue boxes were forgotten and text would appear from the incorrect side.

There was much discussion about coding and the issues with implementing certain cascading style sheets correctly. Using the correct language for Menu systems was a challenge in that the vocabulary used by software and web developers is often not recognized in another language and so there were some words that could not be directly translated. We had to choose the nearest option which at times did not appear to make sense to us. There was much dependency on those who spoke Arabic with a certain amount of trust as we were unable to understand what was being said on our own website. Don’t ever try to use Google translate to test out whether something makes sense if you want to know what is really there!

We were careful to use icons that where acceptable in both cultures and were wary of using some videos or certain images on our blog that might cause offence as this was a cross cultural project. One of our saddest moments was when we realized that the quality of the free text to speech voice in Arabic was so poor so for the time being we are unable to use it, although it is available. We hope in the future to amend the situation. We also discovered that Windows 8 does not offer the complete switch for everything from English to Arabic as they do not have an Arabic text to speech voice available at present.

Without the help of our Arabic postgraduate students we wouldn’t have been able to undertake this project as none of the developers spoke Arabic. We also had the support of the Mada Centre for testing, which was crucial for the further development of the toolbar. However, it was noted that the Acapela voice used by the toolbar for the text to speech did not have a Qatari accent and this remains an issue although it came out best in the user testing.

We also had to develop a completely new Arabic dictionary as the Arabic version of Wiktionary was so poor. The new online dictionary offers both definitions and stemming and is the first of its kind.

We were lucky enough to be able to integrate an Arabic word prediction program called AIType and have embellished the spell checking feature with the help of several free vocabulary lists and Maraim and Nawar’s support.

It is important to remember that text in Arabic tends to need more space, especially if diacritical marks are used as it is a cursive script and needs a very clear font. There were several other items of importance that we learnt from Fadwa’s work and these have been written up on the blog under the title “A framework that might help those developing Arabic software and websites”.

Clicker 5

Jonathan Reed and David Banes look at the experience of collaboration to bring Clicker to an Arabic market

In November 2010 Crick Software and Mada (Qatar Assistive Technology Center) began discussions about the use of Clicker 5, Crick’s flagship reading and writing support software, in the Arab speaking world. David Banes, then Deputy Director at Mada, wanted to explore how to make it easier for Arab users to use Clicker and how we might help them share resources. At the same time Jonathan Reed, International Business Manager at Crick, was starting to explore the Gulf region as a potential area for export growth and exhibited at BETT Middle East 2010 in Abu Dhabi.

During initial discussions Crick and Mada identified the different areas of Clicker 5 that would need to be localized for Arabic users, taking both culture and language into consideration. This did not necessarily mean a full translation of the program, rather a version of the software with Arabic resources and Text-to-Speech as a default. We decided that the best way forward was to work in partnership to create an Arabic version of Clicker, with Crick providing the technical development resources and Mada the skills to be able to localize the various resources for Arabic use.

In March 2011 Mada decided to formalize the process and invited a number of manufacturers to submit a proposal to develop assistive technologies to support Arabic speaking people with a disability. The project plan Crick submitted included details of the financial and non-financial support that was to be required from Mada for the localization and launch of the Arabic version of Clicker in Qatar. We agreed that both Crick and Mada would provide their time and expertise to localize the resources at no cost and in return Mada would provide a copy of Clicker 5 to all Qatari public schools.

Mada accepted the proposal and we then agreed the resources needed, timescales and milestones for the project. After agreements were signed work commenced on the project in June 2011, with Mada’s staff translating the resources and Crick Picture Library (1800+ curriculum-based graphics), Crick’s artist drawing new graphics to add to the library and its developers testing the resources and compiling an installer that included all the components.

As Clicker 5 was the first Arabic localization project that Mada was involved in we spent a great deal of time liaising with each other to ensure that everyone understood what was needed. This included a face-to-face training session with Jonathan in Doha at the beginning of the development phase for all Mada staff involved.

Throughout the project we faced a number of interesting challenges, with one of the main issues being the variety of colloquial Arabic use between people from different countries in the Middle East and North Africa. This became particularly obvious when translating the names of the graphics found in the Crick Picture Library – this feature is used to enable students to write using words and pictures, with the images instantly appearing when a word is typed. However, the ‘instant picture’ facility only works if the word is spelt correctly, so a lot of time was spent agreeing on which variation of a word to include with many of the graphics.

In written Arabic it is possible to see words written without vowel signs in everyday use, e.g. in general publications and on street signs. The Arabic Text-to-Speech supplied with Clicker 5 is a high quality speech engine created by Acapela, the world leader in speech synthesis software. To get the software to pronounce words correctly they have to be written with the vowel signs included, as is the general practice in learning materials, and end users (teachers, therapist, students etc) therefore find it difficult to understand why the software occasionally mispronounces words.

Just eleven months after our initial discussions, and following four months of collaboration on the project, Crick and Mada met all the deadlines and Clicker 5 Arabic was launched successfully at Mada’s offices on October 19th, 2011. Mada has run regular training sessions on Clicker since its launch and is now working with teachers to build a repository of resources for use by Arabic speaking people with a disability across the world.

Looking back on the experience leading to the successful launch there were some interesting challenges that we needed to overcome. The first relates to the process of working together, throughout the process we arranged phone calls and regular reports on progress, whilst these were successful they lacked the opportunity to look at some of the issues in greater depth as they emerged. If there had been the chance to meet face to face during the timetable some of the issues that emerged late in the process might have been averted or mitigated.

Really understanding the patterns of activity from each other’s organizations was also important. The impact of working with a three hour time difference, with different weekends, and allowing for the differences in public holidays, especially the impact of Ramadan on available time.

This mutual understanding can be extended still further in the light of experience. Planning beta testing during the summer, when many people had left the country and during a period of high temperatures that saps volunteers enthusiasm, is probably something to mark down to experience.

In the end the success of the project was down to our shared commitment to make it happen, we learned to be flexible and to listen very hard to each other to accommodate those local needs. The result was a very successful project that has spread throughout schools in Qatar and has been well received throughout the region.

Unit 11 Resources

YouTube video about the AT Framework for Localisation(link is external)

Technical Toolkits

The GALA LT Advisor ”is an interactive directory of tools and technologies related to translation and localization”. http://www.gala-global.org/LTAdvisor/(link is external)

Responsive Design Techniques: A resource provided by Mozilla Firefox with links to web pages describing how website can be developed to suit different viewing technologies such as the mobile phone browser as well as the desktop computer browser. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-(link is external)

US/docs/Web_Development/Responsive_Web_design (link is external)

Cultural Support

Cultural Crossing - A community built guide to cross-cultural etiquette & understanding with advice on over 200 countries –http://www.culturecrossing.net/about_this_guide.php(link is external)

The Localisation Research Centre (LRC) Established in 1995 at University College

Dublin http://www.localisation.ie/(link is external)

Legal Support

UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities signed by 153 countries by 2012 and ratified by 114 countries (including EU and all member states) addresses in many parts eAccessibility, Assistive Technologies and Design for

All. The normal link appears broken: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml(link is external) but it can also be found at http://templatelab.com/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/(link is external)

eAccess+ wiki on EU legislation and policy on eAccessibility - “an overview to key policy and legislative resources at European and national level. Area and technology specific legislation and policy issues can be found in these sections on the eAccess+HUB.” http://hub.eaccessplus.eu/wiki/Legislation_and_policy_on_eAccessibility(link is external)

Standards and Guidelines

The GALA Standards Initiative – “promotes the effective use of standards for international and multilingual content, builds awareness of best practices for their implementation, and helps the localization community make open standards work.”http://www.gala(link is external)global.org/gala-standards-initiative(link is external)

ISO/TC 37/SC 5 Translation, interpreting and related technology - The ISO standards on localization services have yet to be completed but this site provides evidence of the progress.http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards_development/list_of_iso_technical_com (link is external)mittees/iso_technical_committee.htm?commid=654486(link is external)

The W3C Internationalization (I18n) Activity works with W3C working groups and liaises with other organizations to make it possible to use Web technologies with different languages, scripts, and cultures http://www.w3.org/International/(link is external)

Unit 12 Glossary

Accents: in written language these tend to help those reading text to pronounce the word correctly. They are the diacritics seen as glyphs or marks above and below letters in French and several other European languages as well as those based on Hindi, Arabic and Thai scripts.

Alt Tags and Accessibility : Webaim offer advice about the appropriate Use of Alternative Text and many other technical hints and tips to help with making web pages more accessible to those with disabilities. http://webaim.org/techniques/alttext/(link is external)

American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII): based on the English alphabet that encodes 128 specified characters - the numbers 0-9, the letters a-z and A-Z, some basic punctuation symbols, some control codes that originated with Teletype machines, and a blank space - into the 7-bit binary integershttp://www.asciitable.com/(link is external)

AT or Assistive Technology: Assistive Technology (AT) is any product or service designed to enable independence for disabled and older people. (User group consultation at the King’s Fund, 2001). For other definitions:

Bidi or Bidirectional languages: Languages that are written from right to left but may have some text and numbers that are written from left-to-right as in English. Languages include Arabic, Hebrew and Farsi. http://www-01.ibm.com/software/globalization/topics/bidi/(link is external)

Character: In this context it is a single mark or symbol used to represent a word, letter or number in a written language.

Character encoding: machine-readable code that can be mapped against individual or sets of characters such as numbers or letters to present it on the screen as readable text.

Cursive: Joined up writing as in handwriting but in Arabic and Cyrillic languages the script may also appear joined when digitised.

Demographics: human populations – their size, density, statistics relating to a wide range of subjects such as sex, age, gender, religion etc. They are often provided for each country and used by businesses as a way of researching into the need for certain products etc. or governments for supporting services and policies.

Diacritics: These are marks or glyphs that are used to support pronunciation such as the sounds of short and some long vowels in Hindi Thai and Arabic. They may also represent double letters and in older texts such as the Quran, there may be additional super scripts and letter merging between word boundaries.

Diglossia: This is where there are two versions of the same language used side by side by a local population – local conversational Greek and Classical Greek. One may be the local dialect and the other a standardised form that might be heard on the television news or read in books. Another example is Classical Arabic in the Quran or Modern Standardised Arabic as seen in papers and on the internet and the colloquial Arabic spoken across Morocco, Egypt, Syria and the Gulf that all differs sometimes linguistically as well as in accent.

Font: In computing terms a font is seen as a typeface where letters, characters or glyphs that make up the text on the screen can be adapted to suit the user by size and weight. The style of the font has a name such as Times New Roman or Arial.

Globalisation: In terms of development of products this process allows items and services to be used across the world with a minimal amount of change.

Glyph: A mark on a surface such as stone, paper or that has been digitised and can be seen as a stroke within a character or a complete letter as used in written text.

Internationalisation: is the process by which products are developed so that they can be easily adapted to suit local needs.

Localisation: development and adaptation of services and software, websites etc suitable for use in a certain locale – environment. setting which requires cultural as well as language and possible technical changes.

Print Impairment: having a difficulty reading text based or print materials. This may be due to a visual impairment or low vision, dyslexia, literacy difficulties or a physical or other cognitive difficulty making it hard to access text. Those who have a severe hearing impairment or have been deaf from birth may also have literacy difficulties.

Sans serif: without serifs – fonts without small lines or tags often at an angle on the end of each part a letter – A comparison of the sans serif fonts

This is an example of ‘Arial’ font – sans serif

This is an example of ‘Times New Roman’ font – serif

Screen Reader: A program or app that will read aloud all that can be viewed on the screen of a computer tablet or other mobile device. This type of program can be an essential assistive technology for those who are blind or have very low vision. May also be useful in a hands free situation.

Responsive Design Techniques: mainly used to describe the need for designs that will work for web pages that are viewed on the mobile phone as well as the desktop computer. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-(link is external)

US/docs/Web_Development/Responsive_Web_design (link is external)

Unicode: “Unicode provides a unique number for every character, no matter what the platform, no matter what the program, no matter what the language.”(http://www.unicode.org/standard/WhatIsUnicode.html)(link is external)

UTF-8: Unicode Transformation Format 8-bit is a variable-width encoding that can represent every character in the Unicode character set. It works with older codes such as ASCII and allows those working on the web to represent many more characters and symbols than were feasible with the older systems.

Unit 13 One page summary of Key Points for Localizing AT

Unit 14 Operating systems and Localization

Windows

Microsoft offers a multitude of resources for localization support in both desktop and mobile environments. The Microsoft Globalization Step-by-Step Guide is a good start for all Windows developers, it contains fairly non-technical information about the localization process.

Microsoft’s .NET environment fully supports localization and incorporates a fallback hierarchy for localization where a default locale is defined, for example “en” for English. Consider a software with support for English, French, Modern Standard Arabic and Qatari Arabic which is opened in Qatar, then the Modern Standard Arabic resources will be loaded the default English resources thanks to the hierarchy system.

English (“en” default)

| |

Arabic (“ar”) French (“fr”)

The language codes used by Microsoft corresponds to an older standard ISO 639-1, the latest ISO 639-3 contains many more languages and variations, for example afb in ISO 6393represents Gulf Arabic.

Microsoft’s guide to localization in ,NET is a good read, Windows Phone localization is very similar to desktop localization, but Microsoft do provide the guide Localization best practices for Windows Phone .